Content in dialects is booming on social media, but is that enough to save them from extinction?

Qian Shengdong has over 1.5 million Weibo followers, but perhaps less than 30 percent of them can fully understand everything he says in his videos.

That’s because the 34-year-old vlogger’s content, which features him personifying different districts of his native Shanghai or dressing up as a stereotypical local auntie, is not always in Mandarin Chinese (Putonghua), but often mixed with his local dialect: Shanghaihua.

To his fans, Qian, better known as G Sengdong, the transliteration of the dialect pronunciation of his name, is an ambassador of Shanghaihua and contemporary local culture. But off-camera, he rarely speaks the dialect with the team of interns who work on his videos, mostly Shanghai locals born around the year 2000. “It would be weird if I spoke Shanghaihua and they replied in Putonghua,” Qian tells TWOC over the phone. “Half of them don’t speak the dialect at all.”

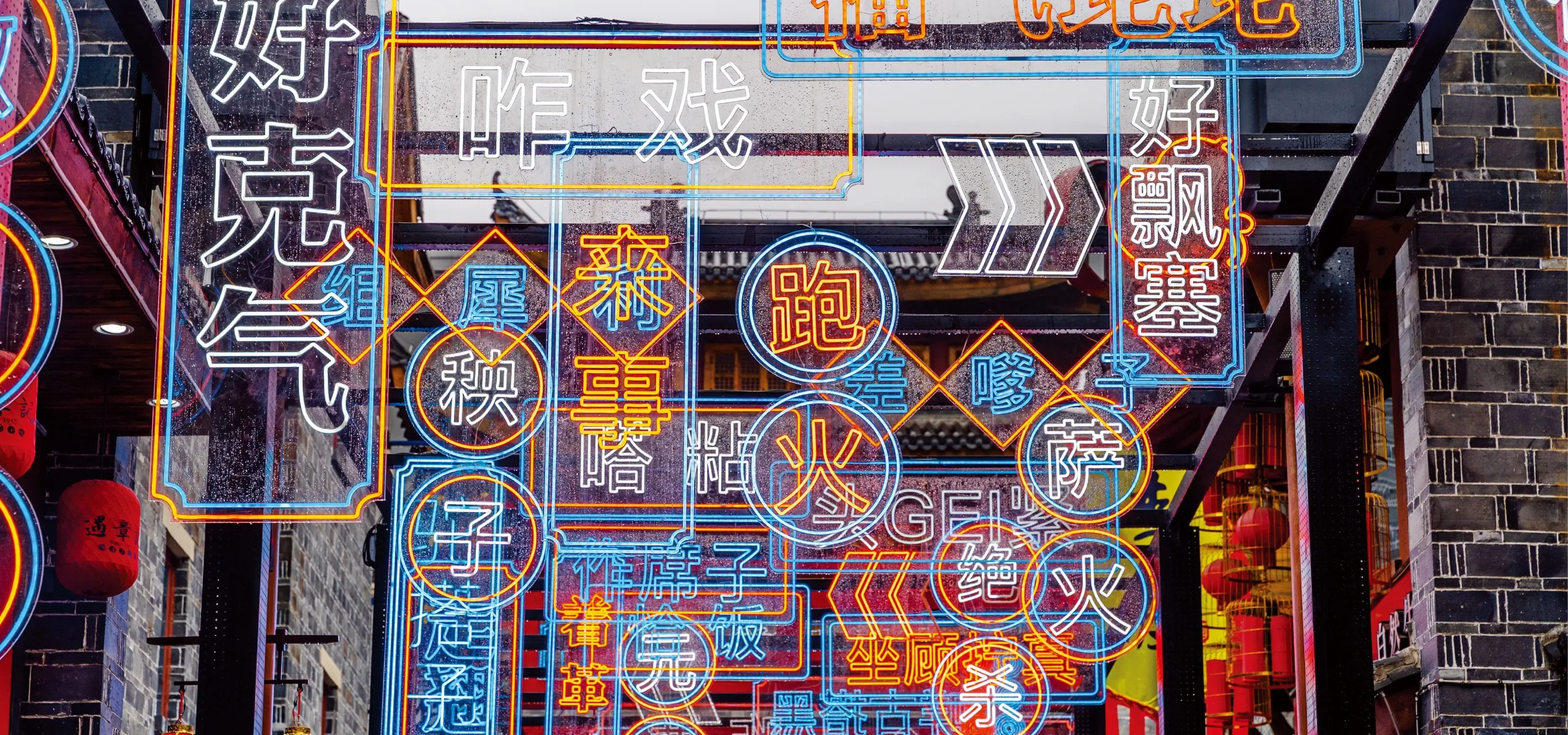

Qian’s videos are part of a growing trend online of Chinese content in dialect, or fangyan (方言), spurred by social media platforms that have made it easier than ever for fangyan speakers to connect with local audiences and even appeal to those who don’t speak the dialect.

But while fangyan videos may be becoming more popular, and the government is belatedly seeking to preserve dialects as essential parts of local culture, decades of Putonghua promotion in schools and official contexts has seen the use of many of China’s hundreds of local dialects decline significantly. Putonghua, the official national language now spoken by 80 percent of the population, is still perceived as a gateway to better employment prospects, social and geographic mobility, and national unity.

In recent years, viral videos on social media have popularized non-Putonghua phrases like the word yue in the Henan dialect, which means “to vomit” and was rediscovered in 2020 supposedly because of the 2012 film Just For Fun. Meanwhile, qiafan, a phrase that means “eat food” in many dialects including Xiang and Gan (dialect families mostly found in Hunan and Jiangxi, respectively), became popular online around 2019, with its meaning extending to a way to mock people who do things they are not proud of for a living.

In May this year, a video of a 29-year-old migrant worker named Cai Jinfa proudly shaking his blond mullet and lip-syncing to “I Am From Yunnan,” a 2020 song featuring vocabulary in the Lisu language and repetitive beats, inspired people from all over China to follow suit, adapting the song to their own dialects (one version even features animated Terracotta Warriors singing in the local dialect of Chang’an district in Xi’an, Shaanxi province). In just a few days, the original video received more than a million “likes” on short video platform Kuaishou, while spin-off posts featuring the hashtag “I am from Yunnan” on Douyin, China’s TikTok, accumulated more than one billion views.

Create a free account to keep reading up to 10 free articles each month

Speaking Up: Can Social Media Save China’s Dialects? is a story from our issue, “Public Affairs.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.