By blending tradition with modern pop culture, northeastern “errenzhuan” was catapulted into the big leagues of Chinese showbusiness—but at what cost?

It is ten minutes before curtain-up, and the Master of Ceremonies of the Dongbeifeng Errenzhuan Theater in Changchun, the capital of Northeast China’s Jilin province, is very happy to see a foreign face in the audience. “England! Football! Oh yeah!” he shouts in English to TWOC with a laugh while enjoying a cigarette with friends.

Behind him his theater is lit up like a Broadway stage. Lamps illuminate full-length posters with enticing action shots of the night’s performers, while a suona, a shrill double-reed horn, squeals to a recording of a thumping electro beat from hidden speakers. “I was at the Jilin Academy of Arts. Actually, how about you write Communication University in Beijing? That sounds better,” the MC asks.

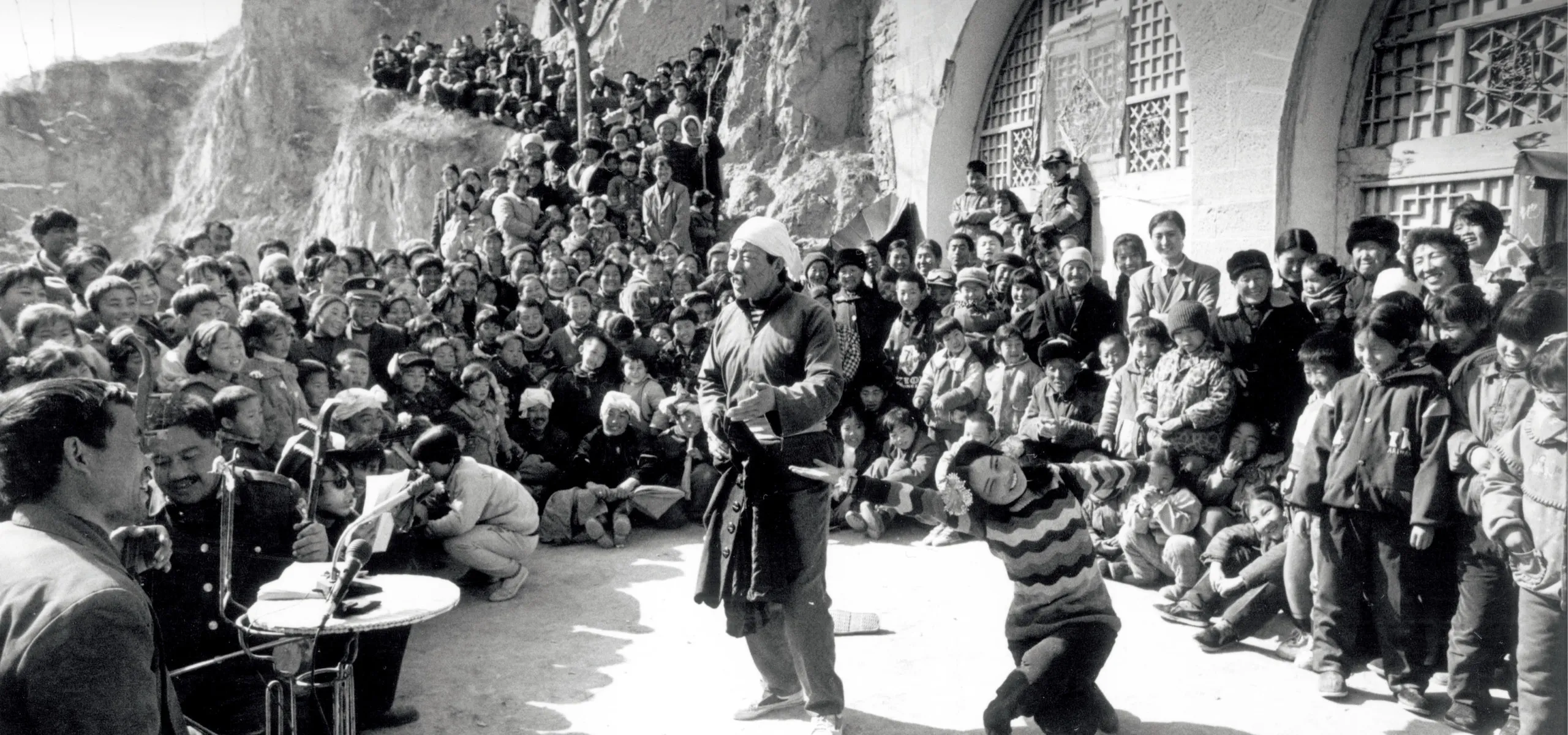

Tonight, it’s all about buying low and selling high—how else to get the bodies in the seats? As audiences in Dongbeifeng’s house laugh along to jokes on stage about female body image or other current social kickers and applaud with plastic “clappers”—hand-shaped noisemakers the theater provides specifically for that purpose—it’s easy to believe that errenzhuan (二人转), a folk performance combining vaudeville and Chinese opera, has escaped the decline that most traditional opera and performing arts seem fated to go through in modern China.

Yet there’s a price to this strategy of reviving a traditional art by catering solely to audience tastes. As the northeast’s most popular cultural export, errenzhuan is viewed fondly, as indispensable a part of Dongbei culture as freezing temperatures and over-drinking. To others it’s a vulgar relic of a more backward time, when audiences were only entertained as they were unsophisticated and didn’t know any better. Competition amongst actors is fierce, while their performances must balance between the coarseness that first made the genre popular, and not re-sparking the offence that caused it to fall from grace.

Errenzhuan, literally “two-person rotation,” allegedly originated in the sketches performed on urban streets, or given as private performances for northeastern families while sitting around the kang (heated brick bed) after a day’s work. In a typical performance, a man and a woman would sing scenes from literature or folk tales, with dance and coarse banter. Performers would play multiple characters, and they were usually not professionals—instead, they were ordinary peasants making ends meet when there was no work in the fields.

Create a free account to keep reading up to 10 free articles each month

Make ’Em Laugh: How a Northeast Folk Performance Escaped Decline is a story from our issue, “Access Wanted.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.