The tragic tale behind China’s national call to arms

When it comes to national anthems, most countries are stuck with patriotic dirges or paeans to monarchy. Compared to these, China’s “March of the Volunteers” (《义勇军进行曲》) is a stirring piece, a cry to resistance, a call for national pride, and a martial anthem. But the history of the song, and the tragic fates of its creators, speaks to the complicated and bloody appropriation of patriotism by the State.

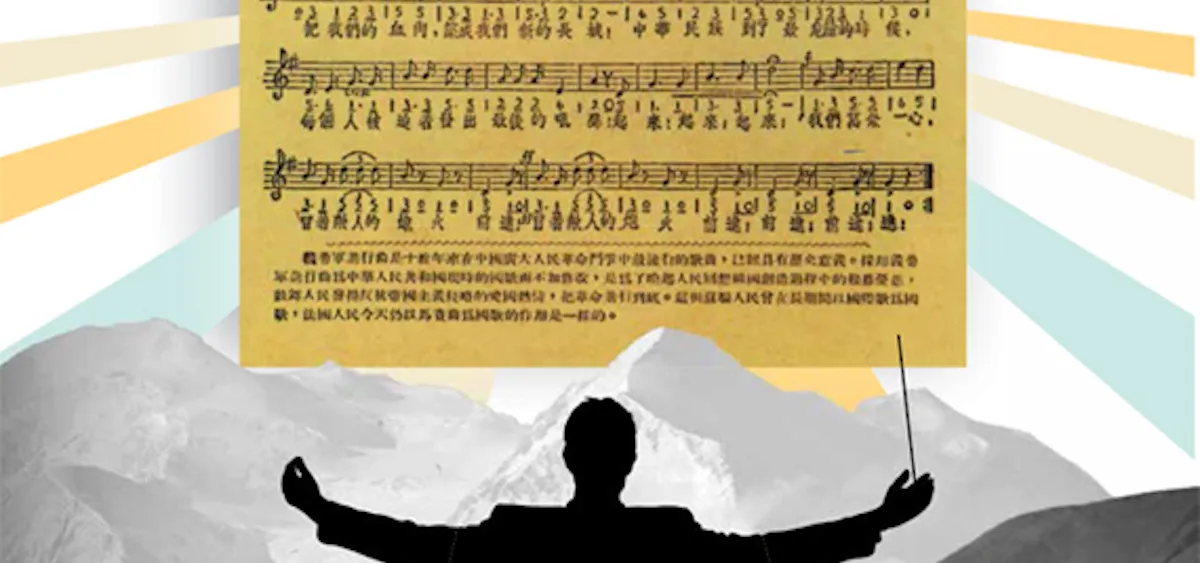

“March of the Volunteers” started as a film number, composed in 1934 by young musician Nie Er (聂耳) and established playwright and lyricist Tian Han (田汉). There are plenty of romantic legends about the song’s origins, such as the text being scrawled by Tian on tobacco paper after being thrown into a Shanghai prison by the Kuomintang. The real origins are more mundane; although Tian was temporarily in jail when the song was composed, Nie simply took the last stanza of a long poem, “The Great Wall”, Tian had written for an upcoming play and set it to his own rousing tune.

Shared Genius

Nie and Tian shared similar backgrounds, although, at 35, the playwright was 13 years older than the baby-faced Nie. They both came from educated, upper-class families, Tian from Hunan and Nie from Yunnan. Inspired both by political fervor and nationalist sentiment, both joined the Communist Party in the early 1930s, throwing themselves into Shanghai’s thriving left-wing drama scene. Both were English speakers looking to the West for how China’s traditions and national spirit could be revived. And, like many Chinese intellectuals of the time, their intellectual life was tied to Japan, where they both frequently travelled. Tian studied drama there from 1916 to 1922, and Nie’s brother was pursuing his education in Tokyo. Japan was a looming menace, but it was also an inspiration: an Asian nation that had gone from a backwater to a modern power in a few short decades.

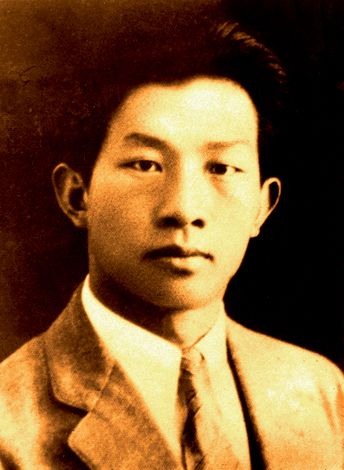

At only 22, Nie was brilliantly talented, capable of picking up almost any instrument. His songs drew upon both classical and popular Western and Chinese forms, a swirl of melodies that produced consistent hit-making. Born Nie Shouxin, he gave himself the name Er, literally “ears,” after a classmate’s nickname bestowed thanks to his musical skills. By 1935 he had written 41 pieces, mostly for theater or film, their titles—“Village Girl beyond the Great Wall”, “Singing Girl Downtrodden”, “Song of the Broad Road”, “Song of the Newsboy”— hinting at their mixture of the sentimental and the political. The songs were themed around the patriotism of all Chinese, from educated overseas returnees to ordinary peasants to the euphemistic “singing girls”.

A young, brilliant musician—was instrumental in the creation of “March of the Volunteers”

Tian was once as much of a prodigy as Nie, composing one-act traditional operas as a teenager. But it was his time in Japan that really made him, exposing him to modern Western dramatists who remade his ideas of what theater could be. He ditched class to go to plays and frustrate his fiancée by his willingness to abandon dates with her for a chance to see a new production. Caught up in politics, he could annoy his literary contemporaries; Lu Xun (鲁迅), China’s greatest modern writer and a friend of Tian’s, once dubbed him one of the “four villains” whom he disagreed with most.

Tian spoke of wanting to be the “Ibsen of China” and ditched the high-toned language of traditional theater for the vernacular, telling stories of ordinary Chinese and putting everyday modern life on the stage; his 1922 play is called, wonderfully, A Night In A Coffee Shop. But he looked to older Western sources as well, providing the first translation of Hamlet into vernacular Chinese in 1921 and Romeo and Juliet two years later. He saw literature as the heart of a nation, quoting with approval Thomas Carlyle’s claim that the British could live without India, but not without Shakespeare. His patriotism was such that, born Tian Shouchang, he renamed himself Han, as in “Han Chinese”.

Tian Han was temporarily in jail when he composed China’s National Anthem

As well as dramatists, his heart was captured by Walt Whitman, whom he saw as the great “bold and pure soul” of the US, the epitome of, in his words, “the song of freedom they (Americans) have composed.” With a practical interest in directing as well as writing, he built stories around elaborate visual and audio effects; the roar of a tiger, the light of a distant mountain, the chatter of a village square. These skills made him a natural for the burgeoning Shanghai film industry, and his passion for the cinema was such that he ruined his eyesight in dimly-lit theaters. Today, many of his plays can seem clumsy, especially after he moved away from the commitment to literature of his early years to a more didactic political approach by the early 1930s, but in the Chinese theater world, he was part of a revolution. His political sentiments led to a brief imprisonment by the Kuomintang; his popularity won him a release.

With this duo of genius behind it, it was no wonder the “March” was a success. It hit the public in two forms; in the film Sons and Daughters of the Storm (《风云儿女》), first screened a Shanghai’s Jincheng Theater on May 24, 1935, and in a popular recording by EMI Music released at the same time. The film was sentimental agitprop with a communist bent, designed to stir up anger against the Japanese occupation of Manchuria and inspire national resistance and revival. The most striking scene is the last, where the “March” is sung as the film cuts to the tramping, sandal-clad feet of the peasant and worker volunteers, along with the formerly decadent intellectual protagonist, hefting rifles and preparing for the national struggle ahead.

The “March” long outlived the film it was composed for. It became one of the most popular songs in China, especially after full-blown war with Japan began in 1937. It was reprinted in newspapers, sung in brothels and pool halls, hummed by guerrillas in the mountains as they prepared for battle. By 1939, African-American singer and Communist activist Paul Robeson was singing it in concert, in Chinese, in sympathy with the struggle against imperialism. While its origins were on the left, it was equally popular with Nationalists as Communists.

But Nie never knew his own success. By the time the film premiered, he was in Japan, visiting his brother in Tokyo. Just two months later, he drowned while swimming in the ocean. Rumors immediately circulated that the death was no accident and that Nie, who may have planned to travel to the Soviet Union after Japan, had been murdered either by Kuomintang agents offended by his Communism or Japanese secret police determined to rub out a source of Chinese nationalism. The truth remains unknown. Dead at 23, the young musician’s remains were brought back to Yunnan three years later, buried at the foot of the Biji Hills where he spent his childhood.

To read the full story click on The World of Chinese Magazine store.