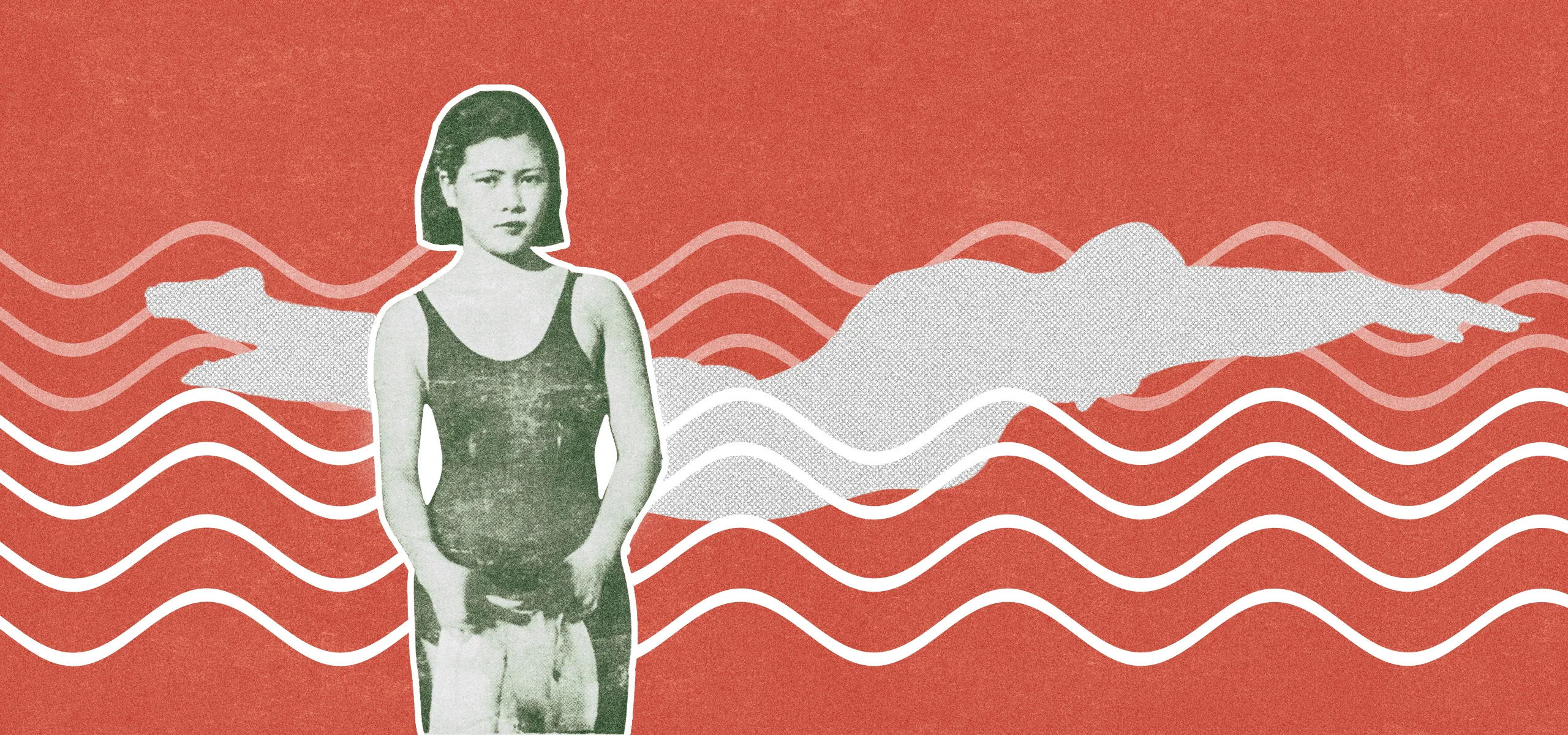

Yeung Sau-king was the first female athlete to represent China at the 1936 Olympics (and also a journalist and spy), but not even medals could protect her from tabloid rumors and misogyny

When Siobhan Haughey punched the wall at 52.33 seconds in the 100-meter freestyle race at this summer’s Paris Olympics, it was enough to earn the Hong Kong swimmer a place on the medal stand. While Haughey is celebrated as the only Hong Kong swimmer in history to earn an Olympic medal, she is also upholding a legacy that stretches back nearly 100 years to a young woman known to the public by her nickname, the Chinese Mermaid.

The Mermaid was Yeung Sau-king (杨秀琼), also known as Yang Xiuqiong or Yvonne Yeung, who rose to fame as a teen and then carried the complicated burden of stardom throughout her life. As China’s first female Olympian, Yeung lived through the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, where she worked as an underground agent for the resistance, only to see her name dragged through the mud of tabloid headlines in a manner strikingly similar to many Olympic stars—and even ordinary women in sports—today.

Yeung was born in 1919 in Dongguan, Guangdong province, and moved with her family to Hong Kong, then under British rule, at the age of 10. Her father was a swimming coach who taught her and her two siblings to swim as children. In 1930, Yeung broke the women’s record in Hong Kong’s Cross Harbor Race, an annual competition that not only was the most popular swimming event in the British colony, but also one that allowed Chinese as well as female participants. Yeung, only 12 years old, completed the swim from Tsim Sha Shui to the Queen’s Pier on Hong Kong Island in 32 minutes and 39 seconds.

Yeung soon began to represent Hong Kong at national sports competitions, which proliferated at the time in China. In 1933, at the Fifth Chinese National Games held in Nanjing, she won gold medals in all five swimming events. The following year, in the Far Eastern Championship Games in Manila, she won four more. The historian Xu Guoqi has written that competitive sports were a key political platform in the 1930s for the Kuomintang (KMT), then the ruling party of the Republic of China. Along with the passage of a national law in 1929 emphasizing the importance of physical education, the phrase tiyu jiuguo (体育救国), meaning “using sports to save the nation,” became a part of the national lexicon.