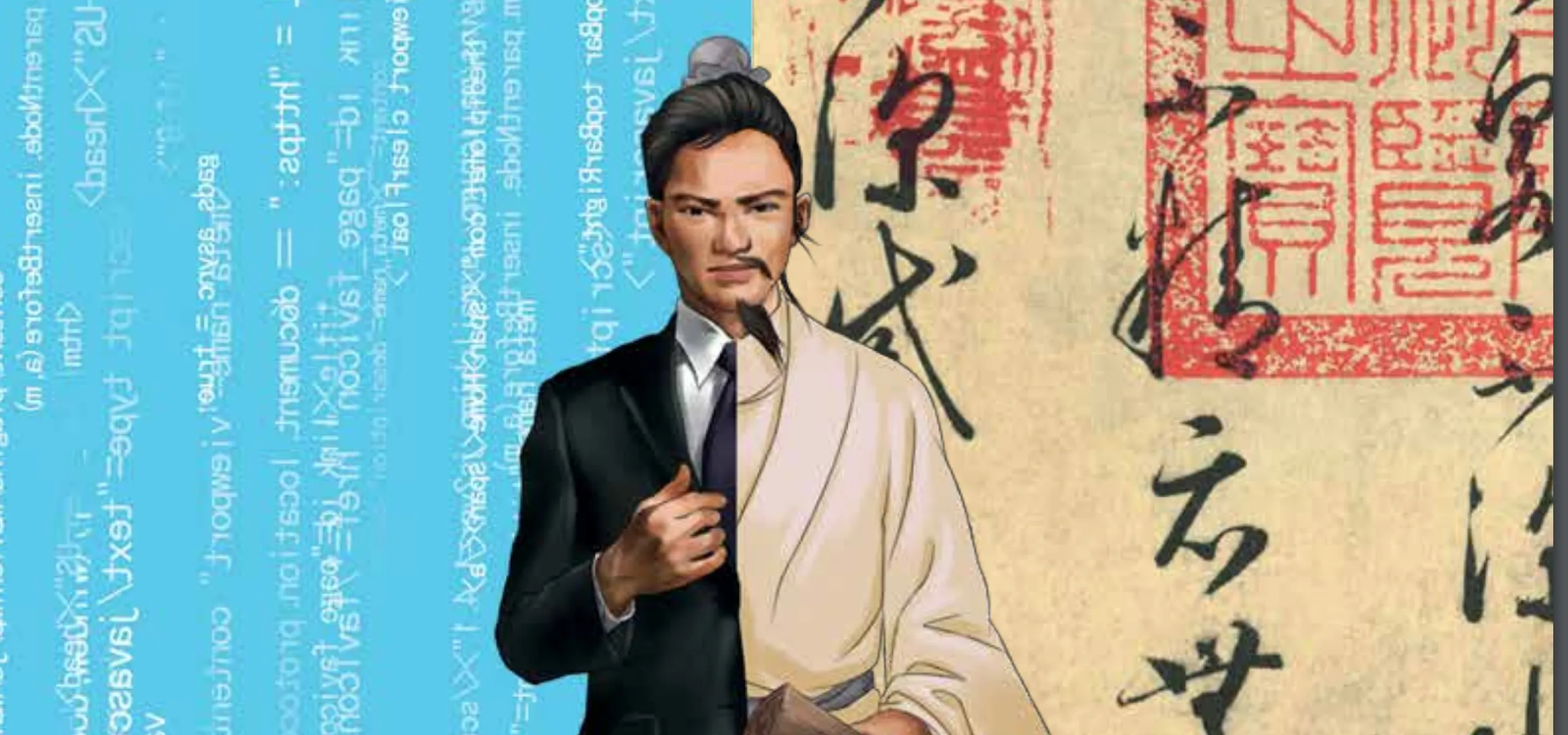

Parents are increasingly looking to ancient Chinese education to prepare their children for the modern world

In a time when China’s best and brightest furiously scramble to become world leaders in any available discipline, from IT and lasers right through to space exploration and robotics, there’s one area where the nation lays clear claim to being ahead of the rest—Chinese National Studies, or guoxue (国学). Naturally, throwing off its competitors through definition alone, the subject exists as an oppositional force to “Western” disciplines and, more often than not, refers to any field of scholarship that is traditional and native to China, be it Confucianism, Daoism, historical writings, ancient poems, medicine, or any number of the arts.

In a sense we could call this study, Sinology. However, whereas Sinology has primarily been underpinned by the outsider looking in—the somewhat fetishized “Western” gaze, which Edward Said famously termed Orientalism—as far as Chinese National Studies goes, the fascination comes from within. “Anything that has withstood the test of centuries and has been passed down today, as long as it has a positive effect in our society, that can be called guoxue—our unique traditional culture,” says Ji Jiezheng, a dignified woman in her 50s wearing, quite fittingly, a dark green qipao and a pearl necklace.

Currently holding 100 students, mostly between four and six years of age, Director Ji’s Chengxian Guoxue Institute is an example of the rejuvenation of guoxue in recent years, its popularity spiking quickly as an academic discipline. Affiliated with the respected Beijing Confucius Temple and Imperial College Museum (北京孔庙和国子监博物馆), the institute is proud of its work in enlightening the young through offering courses including introductory Confucianism, calligraphy, Chinese painting, and various traditional handicrafts for children.

Built in the 14th century under the reign of emperor Chengzong of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1206 – 1368), the construction of the Beijing Confucius Temple was an attempt by the emperor to steady rule over his largely Han subjects. Located just inside Beijing’s Second Ring Road, the temple has long been a place where emperors and scholars pay respect to the most influential thinkers in Chinese history, and it has continued regardless of the capricious rise and fall of any number of dynasties. It still receives considerable worship even today: every morning, a group of small children—girls in pink and boys in blue hanfu (the traditional robes of the Han people)—line up and pay four respectful bows to a marble statue of Confucius, before starting their day at the institute.

In a world that’s obsessed with piano, Olympic-level math, and Disney-inspired English, it seems to many that traditional culture has emerged as a key element missing in a modern child’s development. “The ideal life pattern of us Chinese is to first cultivate the moral self, regulate one’s family, then go on to attend state affairs, and finally bring world peace,” Ji says, quoting the Great Learning (《大学》), a bona fide Confucian classic, adding her own flavor with: “No matter what career the kids pursue in the future, they first have to learn how to be a moral person.”